Sometimes the history of a book can be as interesting as the book itself. I recently came across such a book -- a book that reveals its story through names, dates and places written inside and placed on labels. There is even an interesting piece of paper stuck between the pages -- but I will get to that later.. The name of the book?

Arctic Explorations in the Years 1853, ’54 ‘55 by Elisha Kent Kane, Volume II copyright 1857.

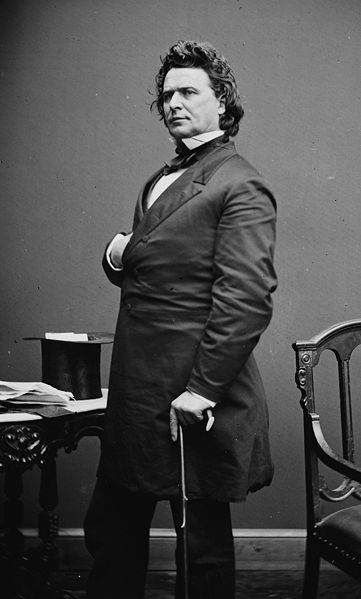

The first owner of the book could have been the U. S. Government, and if not, then likely

John James Abert, Chief of the Topographical Bureau at Washington, and colonel in command of that branch of engineers. Abert is associated in the supervision of many earlier national engineering works and map making projects. It would be appropriate that he would have a copy of Elisha Kent Kane’s book.

|

John James Abert

|

Inside the front of book a light yellow label has been adhered, most likely being the label used when this book was shipped from Washington where Abert was. In the right upper right hand corner: “On Official Business , Bureau Topopgraphy,” then in different handwriting J. J. Abert., Col. Corps. T E. (Colonel of the Corps of Topographical Engineers). This yellow label has a postmark dated Feb. 9, 1857 and says “Washington Free”.

|

Close-up of the postmark

|

It appears to be the actual handwriting of Abert on this envelope when compared to a sample of Abert’s signature found online in a couple of places. Here is one I found in the Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, 1897.

Abert may have even known Elisha Kent Kane. After all, they were both explorers in their own fields. An interesting aside is that Kane died seven days after the postmark found in this book, on February 16, 1857, at the age of 36, while in Havana traveling for his health.

Now we come to the second owner of this book,

Joseph Adams Potter.

|

Joseph Adams Potter

|

The yellow label is addressed to Adjutant J.A. Potter, Survey of the N W Lakes, Detroit Michigan. J A Potter’s name is also written on the title page of the book, along with the date, 1857. At the time Potter received the book he was working as a surveyor on Lake Superior, under then Captain George Meade, a name with which you may be familiar, because he later was a Major General during the Civil War. And this surveyor would also became an officer -- a brevet general -- and a quartermaster in the Union army during the Civil War. Possibly Abert sent Potter this book since his bore similarities to Potter’s own work as a surveyor in the north waters.

The Civil War arrived, and during the war the now quartermaster Potter moved around as soldiers are apt to do. Did the book go with him?

When the war ended Potter continued to act in the capacity of a quartermaster, and in 1867 found himself stationed in Galveston, Texas. Much to his bad luck, there was a yellow fever epidemic while he was there, and he was not spared. One day he was attacked by the fever and on the evening of the third day he was pronounced dying. He had a young wife and an infant son, and they both caught the fever, too. The night Potter was pronounced dying the fever took a favorable turn, and he lived. When he was well enough to leave his bed twelve day later, he found that his wife, his commanding general, and his two body servants were all dead, and no one left but his little boy. His house was in the hands of servants and strangers, and every trunk and drawer ransacked, and many valuables gone. But not the book.

Was the book with Potter in Galveston? We’ll never know for sure, but we can surmise the next and third owner, is Potter’s son

H. W. Potter (Howard), the little boy who survived the Yellow Fever. His label is in the front of the book. H. W. grew up, married, and had two daughters who were born in Streator Illinois. And when H.W. came to Streator the book must have come with him, some time in the late 1800’s.

Now we come to the fourth owner. This is F. L. (Frank) Angier. Just how did he get it? My guess is that he bought it as a used book, or perhaps even was given it. A bookplate in the front of the book shows that Angier lived or worked in Kangley, Illinois, which is not far away from Streator, Illinois, where H W Potter lived.

Angier was also in the army, a Colonel during the Spanish American War, and his name is written in the book, along with

Major General Matthew Calbraith Butler’s name.

My speculation is that during the Spanish American War Angier worked for Major General Matthew Calbraith Buter. Butler’s name is in the same handwriting as Angier’s and it doesn’t appear to be Butler’s handwriting, and so was probably written there by Angier.

Butler has an interesting past, too. From South Carolina, he is a famous Civil War Confederate cavalry officer, related to prominent people of the south, has Revoluntary War heroes as ancestors, and married the daughter of Governor F. W. Pickens. After the Civil War he was elected to the United State Senate, and later appointed a major-general in the volunteer army of the United States, for the war with Spain. That’s when this book must have been in his hands, when he was at Camp Alger, Virginia.

|

Matthew Calbraith Butler

|

After the Spanish American war Angier must have retained the book for some time. Inside the book I found a little slip of paper, a campaign advertisement if you will, for the 24th Annual Encampment of the U. S. W. V. (United Spanish War Veterans). It says . “F.L. Angier, Let us vote for ‘Friday’ on Saturday. Angier ran for some office during this encampment that probably took place in 1923. This means Angier owned the book for at least 25 years, and maybe longer.

So there you have it. A book with ties to one great lake and at least two wars, and some people of note in America’s past.

You may ask, how is it that I have this book. Serendipity I suppose. It was a part of a group of books that sat in an old railroad depot in the Midwest, not far from Streator, untouched, for many years, and finally sold at auction a few months back. Will the book’s history revealed end here? I don’t know, but it has come a long way already.