This entry is from a speech made by James Mitchell Ashley on November 26, 1861, The Rebellion : its causes and consequences : a speech delivered by Hon. J.M. Ashley at College Hall in the city of Toledo, Tuesday evening, November 26, 1861, as found at Cornell University's Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection.

Ashley was was a U.S. congressman, territorial governor and railroad president He was an active abolitionist who traveled with John Brown's widow on the date of Brown's execution. In this speech Ashely attempts to show that the "conflict" was festering for a good thirty years before coming to the surface.

. . . .I have shown that the election of Mr. Lincoln was not the cause of this rebellion, but only a pretext for it ; that for thirty years the traitors have been fomenting treason and have only been awaiting a favorable opportunity to inaugurate it. I have shown that but for the fatal folly and wicked indifference of the North this rebellion would never have come upon us. That we have fed and fostered the viper which is now at our throats, every candid, reflecting Northern man must admit ; when it was an infant, or even when it was but half-grown, the nation might easily have destroyed it, but now by our own fault and guilt it has grown until it has become formidable and terrible. For years we nursed it most tenderly and gave it all the succor and food it demanded. Now outraged justice demands either that we shall destroy it, or be ourselves destroyed by it. There is a law of compensations, a law which is above all human enactments, irrepealable because Divine, which proclaims that "the nation or people who do not rule in righteousness shall perish from the earth," and I believe we are now passing through the trying ordeal which will either establish us as a nation of freemen, ruling in righteousness, or destroy us.

|

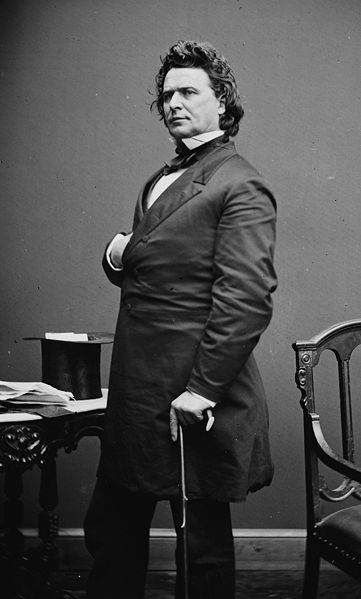

| James Mitchell Ashley from Wikimedia Commons (form the Library of Congress Collection), a Mathew Brady Photo |